It’s no secret that advertising is the key factor in rapid and sustainable growth.

Once you can invest in advertising and profitably buy customers you will no longer be reliant on media or platforms that require a revenue share, such as joint ventures, affiliates, or Amazon. You will take the leap from being someone who promotes a product into someone with a system to create a real business.

In the context of achieving rapid growth, It follows that if you can buy customers consistently, at break-even or a loss initially, but knowing exactly when they’ll become profitable, you will achieve rapid growth and build a large business in the long-run.

This is not a new concept. It’s been used by direct response marketing for decades. It’s a story often told as “break-even on the front end to make money on the back-end.”

But do you know how to measure your advertising campaigns to ensure you achieve fast growth?

The secret is what’s called an “Allowable CPA”.

Here’s how it works…

You’ll likely know, CPA stands for Cost Per Acquisition.

In the context of customer acquisition, CPA is the cost to generate a single new sale. It’s a lagging indicator. It tells you what it cost you, after the fact, to acquire each new customer.

For example: Say you spent $1000 on advertising and generated 10 new customers. You have a CPA of $100 ($1,000/10).

Now, what’s the difference between a CPA and an Allowable CPA?

A CPA is what you actually spent to acquire the customer.

Your Allowable CPA is the maximum amount of money you’re willing to invest in advertising to acquire a new customer.

As you would expect, the allowable CPA will depend on the average selling price of a product or service and the required profit based on the margin. Higher value products will have a higher CPA. For example, a luxury car dealer will have a higher allowable CPA than a local Chiropractor.

The Bigger Picture: Acquisition Vs Monetisation

The key to successful marketing is to acquire buyers at the right price point, then use monetisation processes to drive up the value of each of those customers.

But acquisition and monetisation should be treated as two different stages and tactics of marketing. With two vastly different objectives.

The acquisition stage is all about buying a new customer today at a price which is based on the historical value of a customer.

The monetization stage is all about increasing the average value of each new customer with a variety of offers after they have gone through your acquisition campaign.

Your marketing messages and offers to prospects, large acquisition campaigns, are not going to be the same as your message to customers, small monetisation campaigns. They will be completely different campaigns with different conversion rates.

Here’s the thing…

Allowable CPA is a metric we use for acquisition campaigns. But in order to calculate your allowable CPA, we measure the performance of monetisation campaigns to grow your lifetime value of a customer.

How To Determine Your Allowable CPA

Your Allowable CPA is what you as a business have decided you’re willing to pay to acquire a customer. We calculate our allowable CPA by measuring how much the average customer spends with the business for different periods of time. One month, six months, a year, etc. This is commonly known as measuring a customers’ lifetime value (CLTV or LTV).

Lifetime value (LTV) analysis helps identify which prospects will be most valuable over time and which prospects we should target. For the purposes of most media buying campaigns, the LTV calculation should be done for every single product. For example purchases of product X may have a much different LTV than purchasers of product Y.

This is an important point! You need to think strategically about the products that produce the best customers and lead with them in your promotional campaigns.

For example, the fashion retailer Bonobos’ worked out that men who purchased suits were more likely to come back and make repeat purchases.

The same applies for each advertising campaign. Campaign X may have better backend promotions to campaign Y so it generates a better LTV. Therefore campaign X can have a higher allowable CPA.

LTV analysis should come first and then be followed by an adjustment of the allowable CPA.

If you do not have the data to complete an LTV analysis it’s ok. You can start now then change your allowable CPA during your “journey of discovery”.

For example, a fashion retailer may be running some Christmas sales. They realise that when they acquire a customer during the Christmas sales, the typical customer buys 2 items with an average order value of $150.

Let’s say the retailer’s margin was 40% and they were prepared to invest 50% of that margin into acquiring new customers. The allowable CPA would be set at $30.

6 weeks later the customer returns and makes a $60 purchase. Their LTV is now $210 and the allowable CPA may get increased to $42.

6 Months later the retailer realises that the customers acquired during the December sales are coming back and purchasing from the Winter catalogue. These items, being bulkier, are also more expensive. The average order value is $300.

The best part is that the second and third orders had no advertising expenses as they were acquired via email.

If the retailer was to do a LTV analysis the customer is now $150 + $60 + $300 = $450. Their monetisation phase of marketing has driven up the 6-month LTV.

They can now make a decision based on how aggressive they want to be with their allowable CPA.

It was initially set at $30 to make a profit on the first sale. Given their new knowledge they may go as high $90 as an allowable CPA.

A more typical outcome would be to break-even on the first sale knowing that they’ll make $360 in additional sales over the next 6 months. That means they would set $60 for the allowable CPA and break even on the first sale.

It all depends on what is an acceptable level of aggression within the overall strategy of the business.

Operating with a $60 allowable CPA, compared to the initial $30 allowable CPA would have a massive impact on their speed of acquiring new customers.

More channels would be added, more segments would be targeted and the retailers market share would grow.

Scaling Marketing Campaigns Is Not About Conversion Rate Optimisation

Engineering a campaign for scale is different from engineering for conversion. As long as you’re breaking even the conversion rate doesn’t matter. You could have a 10% conversion rate and be losing money or have a 1% conversion rate and be breaking even.

Scaling Campaigns Is Not About Conversion Rate Optimisation

Allowable CPA Is The Whole Game

Allowable CPA is the biggest indicator of how far your marketing team can scale a promotion. It’s the whole game!

Think of it like this…

Your allowable CPA tells you what you can afford to spend to acquire a new customer. The more you can afford to spend, the more customers you can acquire and the easier acquiring them will be.

If you’re not adjusting your allowable CPA then your acquisition, monetisation and retention strategies are not going to scale quickly.

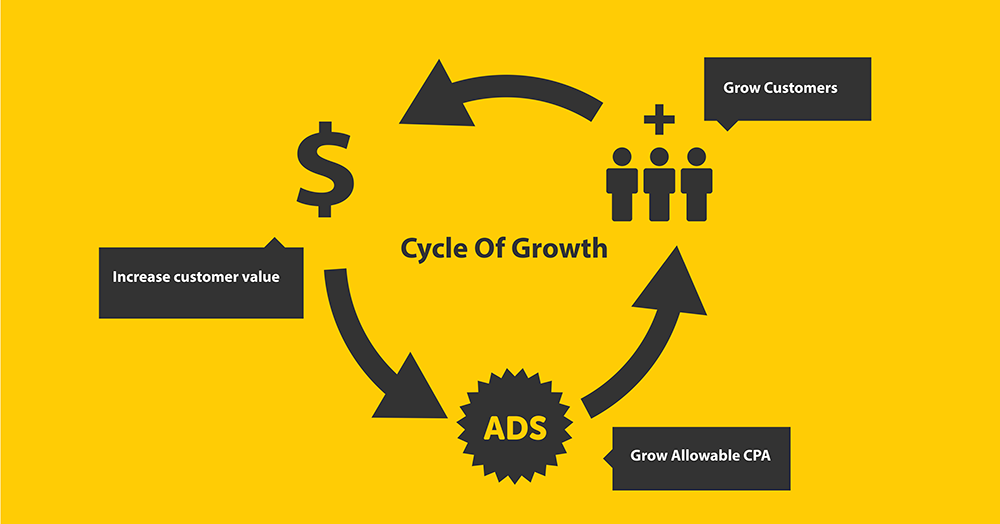

Scale kicks in as customers are being acquired, their value is being increased and that increased value allows you to pay more to get more customers.

It becomes a machine that’s more effective, more efficient and more valuable as it runs. Bringing in more and more customers, growing your allowable CPA. then bringing in more customers, increasing their value again, and round and round she goes.

Levels of Acquisition Aggression

There are typically 3 types of advertisers.

Level 1: Ma & Pa – Spends only enough to allow for a profit margin on every sale regardless of whether it’s a first transaction or tenth.

This is, believe it or not, most people in business. Even when they achieve their allowable CPA targets they still don’t scale their budgets. Their budgets are usually locked in for the year. Unfortunately, this type of planning will never break through the barrier of small incremental growth.

Level 2: Break-even ROI – Spends a maximum of what a customer is worth today… generating a new customer at break-even (i.e. no-profit today but operating costs are covered)

Level 3: Investor (Negative) – Spends a portion of what the customer is worth over the average life of their patronage. Going negative today for the promise of future profits.

One of the first marketers to run this strategy was Jay Abraham, back in the early ’90s, when he was selling an arthritis treatment called “ICY Hot”.

Firstly, Jay knew his customers LTV. His average customer, in fact, ordered six more times a year. Forever!

So Jay decided to spend $3.45 advertising a product sold that sold for $3. It actually cost him a bit more than 48 cents to manufacture, package, and ship out a jar. He was willing to give someone $3.45 to sell a $3 jar. Practically speaking, he really was spending only 93 cents – the 45 cents he lost on every sale, plus the 48¬-cent cost of the product.

Imagine a negative 15% on every first order!

And for that 93-cent loss, he got nearly one million people to try out his product at least once. Three hundred and fifty thousand came back at least six times a year with an average order each time of $10. So for a one-time loss of about $930,000, he added $21 million a year to his business – and over half of that was real profit.

A $930,000 loss – not all incurred at once – produced a $10.5 million annual profit.

I guess the saying is true… “Scared money don’t make money”… but you first need to know your customers LTV in order to make the right marketing decisions.

In A Nutshell… Here’s Why Allowable CPAs Are So Important

Higher Allowable CPA = More New Customers.

The higher the Allowable CPA the more the marketing team is able to spend to acquire new customers… which translates to… the easier it is to acquire new customers.